2007 by Sheila Segurson D'Arpino, DVM, DACVB

Audience: Executive Leadership, Foster Caregivers, Public, Shelter/Rescue Staff & Volunteers, Veterinary Team

Early in my residency program at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine Maddie's Shelter Medicine Program, I set a goal to complete a behavioral assessment project as part of the research requirements for my residency. I spent hundreds of hours observing and performing behavioral assessment tests and read and reviewed research publications regarding the subject. I observed the most commonly performed tests, Sue Sternberg's Assess-a-Pet test and Emily Weiss' SAFER test, as well tests performed at many other shelters. Many shelters which I visited performed a variation of Sue Sternberg's test, adapted to their experiences and requirements. As I became more and more experienced with behavioral assessments, I also became increasingly aware of their limitations. In this article, I will discuss testing and personality, methods to increase the usefulness of the test you are using, the importance (and guidelines for) developing a shelter behavioral program, and frequently asked questions regarding behavioral evaluation of shelter animals.

Behavioral Assessment

Ancient Greeks, most notably Hippocrates and Plato, first formulated the four temperaments (also known as the 'four humours') as ideas regarding character, health and personality. These temperament types were defined as: phlegmatic (reliable, even-tempered), choleric (optimistic, impulsive, and aggressive), sanguine (cheerful, optimistic), and melancholic (quiet, pessimistic). It is from this model that many models of human (and animal) personality and temperament were later developed.

Ivan Pavlov, who most of us remember with regard to classical conditioning and dogs salivating in response to ringing a bell, also evaluated the behavior of the dogs in his studies and argued that different temperament types responded differently to his experiences. He classified his dogs into four temperament types, just as the ancient Greek did. Some dogs were very excitable (easily aroused), but quickly calmed down (good inhibition); these dogs were called sanguine. Some dogs were very excitable, but had poor inhibition of their behavior; these dogs were called choleric. Other dogs were not easily arousable and had good inhibition (phlegmatic) or were not easily arousable and had poor inhibition (melancholic). He stated that phlegmatic and sanguine dogs had 'strong' nervous systems, and choleric and melancholic dogs had less stable nervous systems. It is quite interesting to think about these categories and where some of the dogs in our lives have fit into them, and how these categories might influence how we train and manage our dog's lives.

'Temperament Testing'

I strongly disagree with the use of the term 'temperament testing' with regard to shelter behavioral evaluations. 'Temperament' is based on our genetics and is our innate and natural way of responding to our environment. Character is based on our environment and experiences; it is the habits and behaviors we have developed as a result of our experiences. The combination of temperament and character produce our personality. Human psychologists agree that it is often inaccurate and inappropriate to judge someone's personality based on a one-time meeting or experience. Our personalities are different in different circumstances, and these differences constitute the uniqueness of who we are.

It is virtually impossible for a shelter to assess 'temperament' via a one-time test. Temperament is something that we learn about someone by watching their reactions (or questioning them about them) over a broad range of environments and experiences. Most shelters do not have the time or the resources to do this, and thus they are assessing behavior at a point in time, and not true temperament.

Stress and Behavioral Assessment

As much as we try to enrich shelter pet lives, shelters are a stressful place to be. Stress changes a pet's behavior. Some pets will behave more aggressively when stressed, some more fearfully, and some will be quieter and more inhibited. It is important to recognize the role of stress on our behavioral evaluation results. If a dog is aggressive, is it because she is really stressed? If he is NOT aggressive, is it because she is inhibited due to stress?

Some people feel that it is very valuable to assess a pet's behavior when they are very stressed (and using stress inducing techniques) - they want to know 'what is the worst thing that this pet will potentially do in a home', so that they can protect the public from harm. Some pets will never experience a stress as great as that of being in a shelter (and thus the test is unfairly harsh) and unfortunately, some pets will have a more stressful life than they had in the shelter. There is no way to accurately predict their future experiences and thus no way to accurately create an appropriately stressful test for proponents of this method.

Other people feel that it is valuable to assess a pet's behavior in as home-like of a setting as possible, to attempt to assess a pet's characteristics in situations and environments where they will likely live. This test method is my preference for shelters. Stress certainly influences the reliability of this technique as well, but my opinion is that it is a more 'fair' representation of a pet's personality. We do not yet have research published in a peer reviewed journal regarding commonly used shelter assessment tests. Until this is available, I prefer to err on the side of reducing their stress.

Assessing a Behavioral Characteristic and the Importance of Details - Sociability

When I first started testing, I attempted to behave in a clinical and passive manner toward dogs when I assessed their friendliness toward people. I noticed that many of the dogs did not approach me until I first showed some sign of friendliness toward them. With some shelters, this might give a dog a marginal score and increase the likelihood that they would be euthanized.

I thought about things from the dog's standpoint. 'Max' has been held in a kennel for 5 days. People have rarely shown signs of friendliness toward him and may reprimand him when he tries to say 'hi' (barking or jumping up), but primarily ignore him. Now we take him out and expect him to be calm and friendly, when we are showing no signs of friendliness toward him. In most situations, it is entirely appropriate (and often desirable) for a dog to avoid interacting with us unless we show signs of a desire to interact with them, even though in a test situation some evaluators may consider this behavior undesirable. A person who does not show signs of friendliness has more potential to harm a dog than a human who is friendly to dogs.

Another alternative way to think about this situation involves a dog (that I don't know) who is standing in front of me with a very still body posture (no wagging tail, no relaxed body posture, etc.). This is a dog whom I approach with caution. It is appropriate for a dog who understands human body language to do the same. When I assess sociability, I start by saying a friendly hello to the dog (with words and body language, but not petting) so that the dog knows that I wish to interact with her.

Assessing Behavior - Other Techniques

Because most shelters do not use a test which has been proven reliable, it is important to use other diagnostic aids when evaluating behavior. Behavioral questionnaires for people relinquishing their pets can provide potentially valuable information. Dr. James Serpell and colleagues developed the C-BARQ (Canine Behavioral Assessment and Research Questionnaire) which was designed to provide professionals with standardized evaluations of canine temperament and behavior. This test was recently utilized in shelter research project; more information is available at http://vetapps.vet.upenn.edu/cbarq/. Shelters should also use the day-to-day experiences and evaluation of kennel staff and volunteers who have been trained about canine/feline body language and behavioral observation. Lastly, utilize behavior experts in your area when needed. Expert advice can help shelters to manage individual animals and provide continuing education.

Increasing the Test's Reliability

Training

One person's definition of aggression may be very different than the next. Shelters should have a behavioral assessment handbook which clearly defines the test itself, provides definitions for behaviors, and criteria for outcome decisions. Staff members who perform behavioral evaluations should undergo training about pet body language and the test and receive periodic reviews (to assess inter- and intra-rater reliability). This can be done by videotaping assessments and then meeting to discuss modification of techniques and provide further education.

Performing the Test

Testers should work in teams; it is easy to miss a subtle body language signal when you are standing above the pet and an assistant can keep you safe, and help in the evaluation process. The test should be performed in a room designated for behavior evaluations and a room as free as possible of potentially stressful distractions such as loud noises and other animals. Take all dogs outside to eliminate before testing (a housetrained dog may 'fail' the test because he urgently needs to get outside and isn't interested in interacting with people).

Bias

Don't test dogs that you are biased about. I will not test red pit bulls; I owned a wonderful red pit bull for 15 years and it would be very difficult for me to NOT be biased toward a dog with characteristics similar to that dog. Alternatively, if you don't like Chihuahuas because you have had a bad experience in the past, recognize that you may be negatively biased. Part of being a good evaluator means recognizing your weaknesses and taking steps to make certain they don't reduce your objectivity. Remember that some biases are appropriate. Pit bulls were bred (and many still are) to be aggressive toward other dogs and Belgian Malinois are bred for protection. While not all Malinois are protective, these are genetic traits, and should be taken into consideration when evaluating a dog.

Developing a Shelter Behavior Program

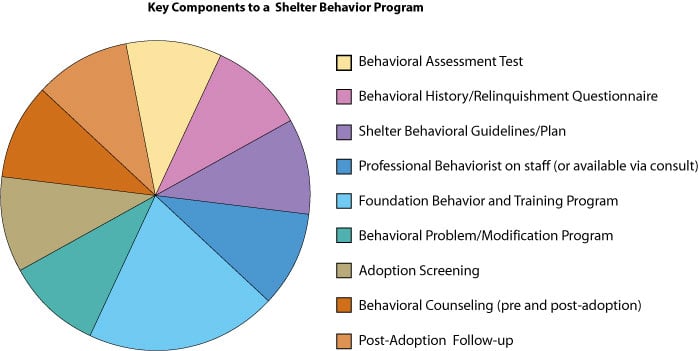

While behavior assessment tests are often the most talked about aspect of behavioral care in a shelter, the test is (or should be) only a small portion of a shelter's behavioral program. The goals of the behavior program should be to: increase the likelihood that a pet will be adopted and stay in its new home, decrease the likelihood that a pet who is a public safety risk will be placed in a home, increase the quality of life of the pets in our care, and decrease the likelihood that pets will be surrendered to the shelter in the first place. Key components of a shelter behavior program are included in the pie chart below. Some of the components have been discussed earlier in this article. The rest are outlined below.

Shelter Behavioral Guidelines/Plan

Shelters should have a detailed Behavioral Plan for the pets in their care. Because behavioral problems are a leading cause of relinquishment, a solid plan for evaluation, treatment, and rehabilitation is crucial to the success of an adoption program. This plan should be devised by a committee comprised of: a shelter manager and/or director, veterinarian, shelter behavior supervisor, a professional pet behaviorist, and a local dog trainer. The plan should include detailed descriptions of all of the items in the 'Key Components' pie chart.

Behavioral Guidelines - Classification and Outcome Decisions

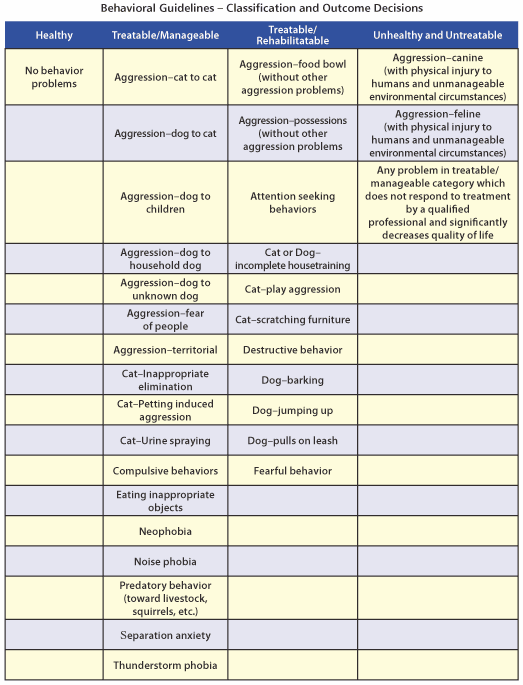

Shelters should have a written scoring or assessment system which will help to guide classification (healthy, treatable-manageable, treatable-rehabilitatable, and unhealthy/untreatable) and outcome decisions. Schedule a meeting with shelter behavior personnel, as well as veterinarians and behavior experts in your community to draft guidelines regarding what problems fit into each category. Utilize your assessment test to categorize and make decisions about pets in your shelter's care. While the behavioral evaluation test certainly has problems (as stated earlier), right now it is all that we have.

Keeping track of results (pet staying in its new home vs. not, and any behavior problems) over time will help us to increase the reliability and accuracy of our test and scoring/assessment system.

Once the pet has been classified, outcome decisions can be made. Although a given problem may be treatable-manageable in a reasonable and caring pet owner, your shelter may not have the resources to properly treat and manage this problem. Thus, it is not manageable in your environment, at this time. Part of being guardians for the animals in our care means knowing what we can and cannot manage and setting goals for the future to save more lives. As an example, I've included a table which categorizes behavior problems for the community I live in. Please note that because of the nature of behavior problems, many of the problems are interchangeable between categories. A pet in the manageable category who does not respond to treatment and whose quality of life is adversely affected could be reclassified as untreatable and unhealthy. A pet in 'manageable' category might be rehabilitatable, but because there is a significant possibility that they are not rehabilitatable (and you don't know until you attempt treatment), they will be classified as treatable-manageable. In addition, because many potentially rehabilitatable behavior problems will require continued maintenance and preventative techniques in the new home, they are classified as manageable.

Foundation Behavior and Training Programs

Because the most common behavior problems of shelter pets are 'simple' problems such as pulling on leash or jumping up, and because these problems are less time consuming to resolve than more complicated problems (but also reduce the likelihood that they will be adopted), every shelter should have a foundation program in place before considering treating more serious problems. The foundation program will increase the adoptability of your shelter population as well as teach staff basic behavioral skills which will be crucial when dealing with problems such as anxiety or aggression.

Behavioral Problem/Modification Program

The 'next step' in a Shelter Behavior Program is a behavioral modification program for pets with treatable problems. This involves hiring and training dedicated staff to treat the pets with problems, providing a detailed and appropriate treatment plan for problems, and a re-evaluation process. As an example, I have defined an identification, treatment and outcome plan for Neophobia.

Definition: Neophobia: persistent and profound fear of new objects in the environment, with poor recovery after exposure. No fear of known objects in the environment. Behavior is manifested as severe avoidance, escape behavior or anxiety.

Treatment:

- Create consistent and routine structured environment

- Reduce kennel stress (provide hiding place in kennel, reduce access to things which increase dog's stress)

- Nothing in Life is Free- dog must work to earn anything it wants (food, attention, access to outdoors, etc)

- Teach 'coping skills' to increase dog's feeling of control over her environment

a. Clicker training

b. 'Check it' command to teach safe way to approach scary items - Medications- anti-anxiety medications may not be necessary in all cases, but dog cannot be categorized as unhealthy/untreatable until medications have been provided for a minimum of eight weeks.

- Trainers must keep a daily log of treatment and behavior modification.

Re-evaluation: Training log and treatment plan must be reassessed and, if necessary, modified once weekly. Dogs who are not making significant progress at one month MUST be started on anti-anxiety medications (if not already on them). All dogs in treatment must be reviewed by training committee once monthly.

Outcome: Dogs that respond to treatment (reduction or elimination of anxiety) can be placed up for adoption and their status identified to adoption staff. Dogs that show progress after eight weeks but are not ready for maintenance will receive continued treatment pending behavioral review. Dogs that do not respond (display significant anxiety which drastically impacts their quality of life) after eight weeks of behavioral modification and drug therapy will be euthanized.

Adoption Screening

Matching pets to an appropriate adopter is a crucial aspect of successful rehoming. adopters must be fully aware of the problem they will be managing and capable of following treatment guidelines. The adoption counselor must also be adept at matching people with the type of pet that they want. A person who is a great candidate for managing a particular problem likely won't be successful if they don't feel a connection with their pet (which is often based on the pet's physical characteristics as well as personality).

Adoption and Behavior Counseling

Most behavior problems are 'manageable' and not 'rehabilitatable', when we are considering sending them to a new home. Even a 'simple' problem such as pulling on leash may recur if treatment of the problem is not maintained in the new home.

All pets with a successfully treated or managed problem must be identified so that appropriate adoption counseling is provided to the adopter. Maintenance requirements (to prevent recurrence) must be explicitly defined for adoption staff and potential adopters. All dogs with a treatable-manageable problem must receive behavioral counseling before AND after adoption. A shelter behavioral modification and training program is useless without proper behavioral counseling for the adopter.

Follow-up

A follow-up program ensures continued counseling for ongoing problems, and assesses the accuracy of the behavioral assessment test and program. For pets without problems, I recommend a follow-up telephone call at three days, three weeks, three months, and one year post-adoption. For pets with problems, I recommend a follow-up telephone call at one and three days, and a follow-up visit at one week, one month, and three months (or whenever is needed). Phone calls for healthy pets can be conducted by trained volunteers, who refer problems to behavior staff. Follow-up calls and visits for pets with problems must be made by trained staff.

Frequently Asked Questions

Question: Can doing behavior assessment also help the shelter by providing protection against lawsuits?

Answer: I'm not a lawyer, but I'll attempt to answer your question. Lawsuits and behavioral assessment tests are a tricky issue. If the shelter does not do a behavioral assessment or did an assessment but didn't find any problems, it can claim that they did not know that the dog had a problem (and hopefully their liability is slightly decreased). If they did do a behavioral assessment and found a problem, or have a history of a problem via a relinquishment questionnaire and placed the pet in a new home anyway, there is the most potential for liability issues.

Question: If a dog is food bowl aggressive, should he be automatically euthanized? Or are there ways to work with these dogs to help this behavior?

Answer: It depends upon the shelter and their particular euthanasia policies. Some shelters will euthanize the dog because they do not have the resources to fix the problem, and adoping them out without fixing the problem is a liability risk. Other shelters will treat the problem, and then adopt the dog to a new home after counseling the owners to make certain that they are able to continue to maintain the treatment plan.

We can teach them to not behave aggressively around the food bowl (in this scenario, assuming that the pet has no other problems) by desensitizing and counter-conditioning them to people coming near (and then handling) their food bowl.

Question: Can you assess cat behavior? Do many shelters do a cat behavior assessment test? I think that overt aggression would be obvious, but I feel like there is a whole range of cat behavior that could be interpreted in multiple ways. I feel like cat behavior is so much less defined then dogs, and I was wondering if you make any special adaptations to your standard test when you apply it to cats.

Answer: Although it is certainly valuable, very few shelters perform cat behavioral assessment tests. The test I use was originally created by Lee et al., 1983. California Veterinarian 3(supplement):23a-24a. It was adapted by Siegford, Walshaw, and Bruner & Zanella, published in Anthrozöos, and then modified by me based on my experiences evaluating cats in shelters.

I use a different test for cats than I use for dogs, and cats' signals/body language are often different that dogs, but otherwise there are many similarities. Many people know less about 'reading' cat behavior and body language, but once you know how to interpret what they are saying, you can use that information to guide treatment and outcome decisions and to match the cat to the best possible home. There are aspects of any pet's (dogs, cats, horses, pigs, etc.) behavior which can be interpreted in multiple ways- which is part of the 'art' of understanding behavior and body language. We use the context of the situation, and ear position, eyes, tail position, vocalizations, etc, to interpret the meaning of the behavior.

Question: I am wondering if you use a point system to compare the overall "adoptability" from one dog to the next based on their performance during the tests or if there are specific tests that they must pass to consider them eligible for adoption? For example, is food aggression an absolute failure of the behavior assessment that indicates they cannot be adopted even if they do well in all the other tests?

Answer: A few years ago, I developed a scoring system to aid shelters in adoptability/euthanasia decisions. Individual shelters would modify the system depending upon their community and which pets are easier vs. more difficult to find homes for in their community. As the shelter improves its programs and develops resources to find homes for more 'challenging' pets, the scoring system will change. Shelters develop the system based upon follow-up at their shelter, to determine which pets are easier to find homes for. Focusing on the easiest to place pets in a crowded shelter will maximize the number of lives saved, because by finding homes for them more quickly less animals die or are euthanized for diseases.

Thus, we can use characteristics of the pet, and its performance on the behavior evaluation test to guide our decisions. You will see a wide variation in 'scoring' (and most shelters do not use a scoring system), depending on the shelter and their resources. Many shelters will try to find a home for a food bowl aggressive dog if the aggression is mild, the dog doesn't behave aggressively in other circumstances, and the dog is small. Most shelters will NOT try to find a home for a food bowl aggressive dog if the aggression is severe, the dog also behaves aggressively in other situations, and if the dog is large (but certainly some would try to find a home for this dog). Obviously there is a huge grey zone in the middle of these two scenarios.

Question: What is the likelihood that a dog will have separation anxiety after being adopted from a shelter? How do you treat this problem? I have a dog that I rescued that has major separation issues...I've been working with him for over a year and he has improved a lot, but he still has the problem.

Answer: When considering separation anxiety in a dog adopted from a shelter, remember that is a chance that the dog had separation anxiety BEFORE it was surrendered to the shelter and that the pet did not develop the problem in the shelter.

Here are some studies that provide information about separation anxiety and shelter dogs:

1. Flannigan G, Dodman NH. Risk factors and behaviors associated with separation anxiety in dogs. 2001. JAVMA. 219; 460-466.

- Dogs from shelters, rescue groups, adopted from vet hospitals or found abandoned more commonly had separation anxiety

2. Takeuchi Y, Houpt KA, Scarlett JM. Evaluation of treatments for separation anxiety in dogs. 2000. JAVMA. 217; 342-345.

- Significantly fewer dogs obtained from shelters (vs. breeders, pet shops, friends) improved - less significant response to treatment

3. Segurson, S, Serpell, JA, Hart BL. Evaluation of a behavioral assessment questionnaire for use in the characterization of behavioral problems of dogs relinquished to animal shelters. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association Dec 2005, Vol. 227, No. 11: 1755-1761.

- Over 40% of dogs being relinquished to shelters exhibited separation related behaviors in their previous home

Dogs adopted from shelters are more likely to have separation anxiety than dogs obtained from other sources, and separation anxiety can be a difficult characteristic to evaluate in shelters. There isn't a validated test to identify dogs with separation anxiety (while they are in the shelter). Ideally, we provide the new adopter with guidelines in an effort to reduce the likelihood that separation anxiety will develop, as well as close follow-up to treat the problem if it occurs in the new home. Treatment of separation anxiety involves behavioral modification techniques and often medication.

Question: Why is behavior testing not done as often on cats as on dogs? Is this because people take dog behavior into account more often than cat behavior when looking to adopt an animal? Or is this because cat behavior is more difficult to evaluate?

Answer: The primary reason that behavioral evaluations are less commonly performed with cats is that cats are less of a liability risk after adoption. Cats are much less likely to significantly hurt someone than dogs are. A second reason would be that many people are more concerned about dog behavioral qualities and characteristics than cats.

In my opinion, cat evaluations should be performed at least as often (if not more often) than dogs. Because cats are much more likely to be euthanized in shelters than dogs, we want to be doing everything possible to make certain that the cats we are placing up for adoption will get adopted quickly- so that we can prevent problems associated with crowding and maximize the adoptability of cats in our adoption areas.

Cat behavior is not inherently more difficult to evaluate. However, many people working in shelters know less about cats than dogs; thus, it is more difficult for them.

Question: Do you perform the same behavior tests in puppies as you do in adult dogs? How accurate do you think puppy temperament testing is? Are there any good tests out there?

Answer: There have been several studies regarding puppy testing (primarily Campbell's test), and unfortunately puppy testing's usefulness is fairly limited in terms of ability to strongly predict future behavior. We do recommend testing all puppies (in the same way we test adults), because if we see significant aggression or other behavioral concerns, it is certainly something we wish to identify and treat. In general, the primary test being used these days is Volhard's test (you'll be able to find it if you do an internet search for 'Volhard puppy test').

If you are adoping a puppy from a litter, in general, you don't want to pick the most outgoing, the most independent, or the most withdrawn puppy. You want a puppy that follows along with the pack, and is also friendly and interested in interacting with people.

Dr. Sheila Segurson D'Arpino

Dr. Sheila Segurson D'Arpino is a pet behavior specialist and is board-certified by the American College of Veterinary Behaviorists. Her interest in animal behavior began in 1988 while volunteering in the behavior department at the San Francisco SPCA. She graduated from the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine in 1996. After a one year internship in medicine and surgery at The Animal Medical Center in New York, she worked as a general practice/emergency veterinarian and went on to enroll in a three year post-graduate Behavior Specialty Training Program at UC Davis, with an emphasis on shelter animals and shelter behavior programs.

Dr. D'Arpino's special interests are aggression, anxiety, and behavioral programs in animal shelters. She lives with 4 dogs and a cat. In her spare time, Dr. D'Arpino is an active member of CARDA (California Rescue Dog Association); Sheila and her dog, Herbie are a certified trailing search and rescue team.