March 2012 by Ellen Jefferson, DVM

Audience: Executive Leadership, Foster Caregivers, Public, Shelter/Rescue Staff & Volunteers, Veterinary Team

Today, the City of Austin is saving 91% of its homeless dogs and cats and is the largest no-kill city in the US. That wasn't the case just four years ago when 44% of the animals coming into the Austin Animal Center were losing their lives. Dr. Ellen Jefferson recounts how she used the shelter's data to figure out bottlenecks in the system and to develop and fine-tune programs to fill in the gaps.

I became a volunteer at the Austin Animal Center (AAC) in 1998 to help save lives with my veterinary skills. It soon became apparent, however, that since the shelter was euthanizing 85% of the animals that entered its doors due to space constraints, the medical help that I provided did not help the sheltered animals leave alive in any larger numbers.

As a result of wanting to make a bigger difference with my vet degree, I founded a low-cost and free spay/neuter clinic, Emancipet, in 1999. The thought was to decrease the number animals entering the shelter through fewer births in the community so fewer would have to be euthanized in the shelter for lack of space.

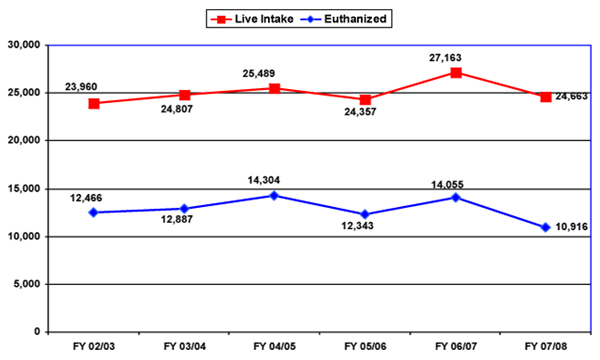

By 2008 and after over 60,000 spay/neuter surgeries, I had expected to see a bigger reduction in city shelter intake numbers. Although there was an initial decrease in euthanasia from 85% to 50% between 1999 and 2001, after 2001 the AAC (the only open admission shelter in Austin, Texas) consistently took in over 23,000 animals and euthanized an average of 50 - 55% of the animals admitted each year. In fact, AAC euthanized over 14,000 animals in 2007, which was a decade record and showed me that my efforts were not decreasing shelter intake or euthanasia like I had hoped.

The other piece of data that was eye-opening to me in 2008 was that the number of AAC live outcomes stayed static at 10,000 per year, year after year, even after budgetary increases. By then, the City of Austin and the Austin nonprofit animal welfare partners were providing substantial community services for spaying, neutering, vaccinations, and wellness clinics; however, the city's live releases had not changed at all in spite of the wealth of community resources that were geared towards lowering euthanasia.

It was clear that the city had a system that was capable of producing no more than 10,000 live outcomes per year, regardless of intake numbers, which meant that euthanasia only fluctuated when intake numbers fluctuated. If intake went up, euthanasia went up. If intake went down, euthanasia went down.

For years, the city had been measuring "inputs" for city performance standards such as the number of spay/neuters performed, the number of microchips placed, the number of rabies vaccines given; and with the large amounts of city and donor funds going into free and low-cost spay/neuter, it appeared to politicians and foundations from a performance measure standpoint that Austin was at the top of its game. The thing that really struck me was that although "outputs" such as euthanasia, adoption, return to owner, and transfers were being documented and measured, decisions to directly impact those numbers were not being driven by their measurement. Funds were never requested to directly improve live outcomes and city staff was not being directed to strive for higher live outcome numbers. In fact, there was no live outcome improvements projected for at least the five years after 2007 and that was apparent as plans for capacity in building a new shelter got underway.

I had spent nine years pouring my heart and soul into spay/neuter and while I knew it was helping the community, I had expected a bigger measurable impact at the shelter. It bothered me that we had no real conclusive studies that showed the impact of spay/neuter on euthanasia in the shelter and that the labors of all my work were not something I could see an impact from in a decade. I felt strongly that there had to be a way to save more lives at the shelter and a more direct way to measure the work that provides that impact. If it takes longer than a decade to see an impact at the shelter euthanasia level through spay/neuter, the work can never be tweaked to have a bigger impact. There had to be a more direct method to save lives that could be measured month-to-month and tweaked quickly if the desired effect is not seen. It appeared that a new and different kind of work needed to be created to really get measurable results on euthanasia figures since it also appeared that all current resources were operating at their max. It was apparent to me that I needed to change what I was doing to effect faster change in the community.

The American Veterinary Medical Association's (AVMA) Demographic Sourcebook dispelled my belief that there were not enough homes. In the Greater Austin Area, AVMA calculates that at least 75,000 homes take in a pet less than one year old each year, and the ASPCA has reported that only 20 - 25% come from shelters and rescues. We only had to find homes for up to 14,000 pets per year. This seemed very doable when 75,000 homes are open each year for incoming pets. Unfortunately, there was no one else willing to create a new program to cause more live outcomes and it was clear that the city was not going to create it from within the shelter. I reached out to Austin Pets Alive! (APA), a local nonprofit that promoted animal advocacy, and asked if I could lead the organization on a resurrected crusade to No-Kill. The board of directors said "yes".

Using Data to Identify and Fill in the Gaps

There were two initial strategies used by APA to increase AAC live outcomes:

- The first strategy was to simply increase the live outcomes at the shelter by promoting adoptions through marketing and customer service. Our thought was that by doing more to promote live outcomes, the euthanasia numbers would decrease. The flaw in this logic was that the city was only capable of getting 10,000 live outcomes through their system of vaccinations, spay/neuter, testing, processing applications, and housing. With no increase in funding or support staff to do more spay/neuter and medical workups, no additional people to process adoptions and no additional kennels to house animals longer, APA's marketing efforts to get one animal out alive simply displaced another animal rather than resulting in a net increase in live outcomes. APA could not overcome the AAC bottleneck in evaluations and medical "make ready" that existed for a decade. It was clear that unless the entire system grew, it wouldn't work to augment only one piece (marketing of animals) and expect a measurable increase in live outcomes. It was also clear that the city had no intention of growing their system.

- The second strategy was to remove the animals from the shelter so that AAC could continue to produce 10,000 live outcomes and APA would have to build its own system to produce at least 10,000 more. It was apparent right from the start that the only way we would NOT displace animals that already had live outcomes was to develop a laser-like focus on the euthanasia list rather than all the animals in the shelter (or any animal in the community). The protocol was set that APA would intervene and help only animals that were definitely going to die without APA's help, usually within hours of being put on the euthanasia list. This was critical for our success because it provided data to easily measure performance and impact on euthanasia in terms of the No-Kill goal. After an agreement was reached with the shelter, the AAC began to provide the euthanasia list an hour before closing each night. If APA did not intervene on those pets' behalf, all the animals would be euthanized before opening the next day. APA's measurable impact could be easily seen and tweaked even on a daily basis, by dividing the number of animals saved by the total number that were set to be euthanized daily. For instance, if there were 100 animals on the euthanasia list and APA saved 10, our impact, and ours alone, was a 10% reduction in killing for that day. That was the kind of measurable impact I was looking for!

Using Data to Develop Programs: Filling the Gaps

As APA examined the euthanasia list each day, we could identify the trends and specify groupings of animals that were being euthanized. With even a month of data on types of animals dying, we could determine the need for specific programs and create the programs to help those animal groups. Analyzing the euthanasia statistics helped us recognize the gaps in Austin's shelter and the community, and design ways to fill them.

The statistics reflected that:

- About 20% of the euthanasia list was made up of healthy dogs and cats, therefore APA created off-site adoption programs to increase the number of adoption venues and thus the number of adoptions. They didn't need anything more than additional exposure.

- Roughly 20% of the euthanasia list was made up of animals that are easily made adoptable and are desirable by adopters. These were animals with mange or kennel cough, minor behavior issues like being scared, or animals with minor injuries. APA created a large-scale foster program to provide short-term foster for these animals as they overcame their minor problems.

- About 20% of the euthanasia list, roughly 1,200 animals, was comprised of orphaned kittens. Historically, neonatal kittens had not been saved because of a lack of experienced foster homes. Thus, APA established a neonatal nursery with all the supplies needed for around-the-clock kitten care. It was designed for volunteers to bottle feed, clean, medicate, and care for the kittens every two hours, and for the kittens to stay in the nursery until fosters were available or until they were adoption-ready. New fosters are trained at the nursery, thus increasing foster capacity for these animals.

- Critically ill and injured pets made up another 20% of the euthanasia list. These pets are euthanized immediately in traditional shelters due to suffering and fear of disease spread. APA created a Parvo Ward for puppies with parvovirus and developed triage protocols to deal with the large number of injuries, fractures, and illnesses that need immediate care. We again built up a large-scale medical foster base for all the injured and ill animals. Convalescing in a home is far better than in a shelter.

- Ten percent of the animals on the euthanasia list was made up of large breed dogs with behavior problems. These dogs are the most expensive in terms of dollars, time, and expertise. APA has saved more and more animals from this list year after year, but is still challenged with developing the perfect program to meet their needs and save the remaining animals. Saving this last group of dogs would bring Austin to a 95% save rate.

- The remaining 10% of the euthanasia list, or 5% of the total intake, was comprised of animals that are truly in need of the dictionary definition of "euthanasia". They are suffering greatly from a condition for which there is no cure, or they pose a significant safety threat to the public.

Using Data to Re-Assess and Fine-Tune Programs

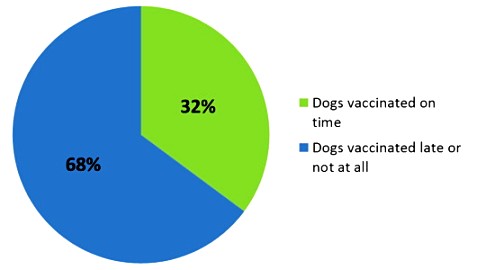

Distemper became a huge problem for APA in 2009 after pulling infected dogs from the city shelter. APA was able to look at the intake data and determine that AAC shelter intake vaccines were missing on almost all of the dogs affected by distemper. This allowed APA to intelligently talk with the city government about the necessity of proper intake vaccinations and the reassessment of the AAC intake protocol. The traditional reaction by a rescue group to a distemper crisis would be to stop pulling animals from the infected shelter. APA didn't stop, but it did work hard to prevent the disease from continuing, and was able to effect change through documentation of numbers.

APA was able to convince city officials that AAC needed to vaccinate before intake 100% of the time, which has led to an almost nil distemper infection rate for the rest of 2009, all of 2010 and 2011.

Since we rescue the animals that would be killed for disease including distemper, we are able to keep close tabs on AAC's vaccination compliance and also the disease infection rates. We also noticed a drastic decrease in the really horrible cat upper respiratory infections as a result.

APA can now save puppies and small breed dogs and even some cats from surrounding communities by utilizing our Austin adoption program because we know we can accomplish an ever-increasing number of adoptions each year. The Austin community's demand for adoping a pet is higher than the supply from AAC, as previously reported by the AVMA's study. By bringing in animals from other shelters, APA is able to prevent adopters from becoming pet store pet buyers and thus save a whole lot more lives. Although there is concern that puppies and small breed dogs will offset the adoption of large breed dogs with behavior issues who still need to be completely saved in Austin, statistics do not reflect that there is an imbalance. More and more of Austin's adult large breed dogs with behavior issues are adopted each year because of improved customer service, pet-matching practices, and behavior modification. That number is expected to increase as funds are raised to put facilities and expertise for handling those animals into place.

APA rescued over 5,000 animals last year. No cat, kitten, small breed dog, puppy of any breed, or large breed friendly dog, including pit bulls, died in the City of Austin in 2011 simply because it didn't have a home. Austin is officially the largest No-Kill City in the U.S. with an annual save rate of 91%.

Ellen Jefferson

Ellen Jefferson received her undergraduate degree from Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas in 1993 and her Doctorate of Veterinary Medicine from Virginia Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine in 1997. She moved to Austin, Texas in 1998 and has worked as an emergency veterinarian as well as in private practice while fulfilling her nonprofit goals in spay/neuter and rescue. She shares her home with her husband and their many "four legged children".